I’ve always been intrigued by cultures that live untouched by modern convenience. Recently, I had an eye-opening experience immersing myself into the Hadza tribe's world near Lake Eyasi in Tanzania. Observing their raw survival skills felt like stepping back tens of thousands of years — from hunting with bows and arrows to savoring wild honey straight from the comb. But beyond the surface, their life challenges how we think about community, survival, and connection to nature.

The Unique Hadza: Guardians of an Ancient Way

Nestled along the wild shores of Lake Eyasi in northern Tanzania, the Hadza people—also known as the Hadzabe tribe—stand as living links to humanity’s earliest days. For over 50,000 years, the Hadza have called this region home, surviving in a way that echoes the rhythms of our ancient ancestors. Their story is one of resilience, adaptation, and a deep connection to the land, even as the modern world presses ever closer.

Life on the Edge of the Savanna

The Hadza live deep in the wild savanna, where uncertainty waits behind every bush. Here, they hunt for food with bows and arrows, tracking animals like rock hyraxes, antelopes, and even baboons. Their days are spent moving through the bush, reading the landscape, and relying on skills passed down through countless generations. As I joined them, I quickly realized what it means to live “life in its rawest form.”

"The Hadza tribe lives life in its rawest form."

Their diet is as varied as the land itself. The Hadza drink water from muddy streams, gather wild honey—sometimes eating it with larvae—and occasionally consume meat that includes animal waste. Every meal is a testament to their resourcefulness and deep understanding of their environment.

Ancient Roots, Recent Contact

Despite their long history, the Hadza’s first real contact with the modern world came only about 150 years ago. Before that, their way of life remained largely untouched, shaped by the cycles of nature and the traditions of their ancestors. Today, the Hadzabe tribe is recognized as one of the last true hunter-gatherer societies on Earth.

The Hadzane Language: A Living Relic

One of the most fascinating aspects of Hadza culture is their language, Hadzane. It is unique among African languages, featuring distinctive click sounds that set it apart from neighboring tongues. Listening to the Hadza speak, I was struck by the musicality and rhythm of their conversations—a living relic of humanity’s linguistic past.

Egalitarian Society: Living Without Hierarchy

The Hadza people organize themselves into small, nomadic bands, usually made up of 20 to 30 individuals. These camps are fluid, with people coming and going as they please. There are no chiefs or formal leaders. Instead, the Hadza practice an egalitarian society where decisions are made by consensus and everyone’s voice is valued. This non-hierarchical structure is rare in today’s world and offers a glimpse into how early human societies may have functioned.

Camp Size: Typically 20-30 people

Decision Making: Consensus-based, with no formal leaders

Social Structure: Egalitarian and non-hierarchical

Facing Modern Pressures

While the Hadza have survived for millennia, their way of life is now under threat. The expansion of agriculture and encroachment on their territory near Lake Eyasi are shrinking the lands they depend on. As more land is cleared for farming and settlements, the Hadza’s ability to hunt, gather, and move freely is increasingly limited. Their unique culture and ancient traditions are at risk, even as they continue to adapt and persevere.

The Hadzabe tribe’s story is not just about survival, but about guarding an ancient way of life in a rapidly changing world. Their resilience, deep knowledge, and commitment to egalitarian values make them true guardians of an ageless tradition.

Hunting and Gathering: Survival in the Wild Savanna

When I walk alongside the Hadza people, I am reminded of a way of life that has endured for thousands of years. Their hunter-gatherer lifestyle is not just a tradition—it is a daily practice of survival in the wild savanna. As one Hadza elder put it,

"They survive by hunting their food with bows and arrows just like our ancestors did thousands of years ago."

Hunting Techniques: Bows, Arrows, and Ancient Skills

The men of the Hadza tribe are skilled hunters, carrying handmade bows and arrows wherever they go. These are not ordinary arrows; many are tipped with a potent poison made from the sap of the Adenium plant. This poison is a key to their hunting success, allowing them to bring down swift and wary animals that roam the savanna. The Hadza target a range of animals, including rock hyraxes, small antelope, baboons, and guinea fowl. Sometimes, I have watched as they stalk their prey with patience, moving quietly through the tall grass or waiting for hours at a waterhole during the dry season, where animals come to drink.

Hunting targets: Rock hyraxes, antelope, baboons, guinea fowl

Weapons: Bows and arrows, often tipped with Adenium poison

Techniques: Stalking, ambush, waiting at waterholes

Hunting is usually done alone or in pairs, relying on stealth and deep knowledge of animal behavior. The skills and techniques are passed down through generations, taught by fathers and uncles through storytelling and participation in the hunt.

Foraging Parties: Women and Children Gathering Nature’s Bounty

While the men hunt, women and children form foraging parties that move through the bush in search of plant-based foods. Their knowledge of the landscape is remarkable. They dig for tubers with sharpened sticks, gather baobab fruit and wild berries, and search for edible greens. One of the most prized finds is wild honey. For the Hadza, honey is more than a delicacy—it is a vital source of nutrition, providing energy, protein, and essential fats.

Gathered foods: Tubers, baobab fruit, berries, wild honey

Foraging tools: Digging sticks, baskets, smoke for honey harvesting

Honey harvesting is a communal event. The group locates a hive high in a baobab or acacia tree. To calm the bees, they use smoke from a smoldering bundle of leaves. Then, someone climbs the tree—often barefoot and without ropes—to reach the hive. The honeycomb is harvested with care, and nothing is wasted. The Hadza eat the honey, larvae, wax, and pollen, making use of every nutrient the hive provides.

Division of Labor and Traditional Knowledge

The roles in hunting and gathering are clearly divided by gender and age, yet both are equally important for the survival of the group. Men focus on hunting, while women and children gather and forage. This division is not rigid; sometimes, skills overlap, and everyone contributes to the well-being of the camp.

What strikes me most is how traditional knowledge is preserved. Children learn by doing—joining foraging parties, listening to stories, and watching their elders. The Hadza’s hunter-gatherer lifestyle is a living link to our shared human past, a testament to resilience and adaptation in the wild savanna.

The Hadza Diet: More Than Just Honey

When I joined the Hadza tribe near Lake Eyasi in Northern Tanzania, I quickly realized that their diet is far more complex than the popular image of honey hunters. The Hadza diet is a true reflection of their deep connection to the land and their remarkable adaptability as one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer societies. Over the next three days, I witnessed firsthand how their food choices are shaped by tradition, environment, and necessity.

Wild Honey: A Prized and Complex Food

Wild honey is at the heart of the Hadza diet and is consumed in many forms. The process of gathering honey is elaborate and requires skill and courage. Hadza men use smoke to calm wild bees, allowing them to collect not just the sweet honey, but also the larvae and wax. This combination provides a unique nutritional profile, with honey offering quick energy, larvae supplying protein and fat, and wax contributing fiber and micronutrients. As one Hadza member explained to me, "They drink muddy water, eat honey with larvas and even sometimes meat with animal waste."

Baobab Fruit, Tubers, and Berries: The Plant Powerhouses

While honey is celebrated, plant foods are the true staples of the Hadza diet. Tubers, which are dug from the ground using simple wooden sticks, are eaten daily and are a major source of fiber and carbohydrates. Baobab fruit, another key food, is rich in vitamin C, calcium, and antioxidants. The Hadza also gather wild berries and other fruits as they become available throughout the year. This high intake of natural fiber from plant sources is linked to the tribe’s low rates of metabolic diseases, a stark contrast to many modern diets.

Wild Meat: Seasonal and Supplementary

Meat is an important but unpredictable part of the Hadza diet. Hunting success varies with the seasons, and the types of animals available change throughout the year. When a hunt is successful, the entire group shares the meat, which can include everything from antelope to birds. Sometimes, as I observed, the meat may even be consumed with traces of animal waste—an example of the Hadza’s resourcefulness and lack of waste. However, meat is not eaten every day and serves to complement the more reliable plant foods and honey.

Adaptability: Drinking Muddy Water and Seasonal Shifts

One of the most striking aspects of the Hadza diet is their adaptability. Water sources are often scarce, and the Hadza sometimes drink muddy water out of necessity. Their diet changes with the seasons, requiring a broad knowledge of edible plants, animal behavior, and the landscape. This flexibility is a key evolutionary adaptation, allowing the Hadza to thrive in a challenging environment for over 50,000 years.

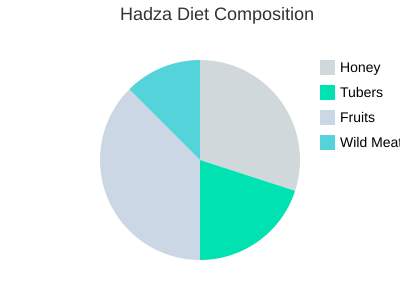

Diet Composition: A Hunter-Gatherer Balance

The Hadza diet is a balanced mix of wild honey, tubers, baobab fruit, berries, and wild meat. Each component plays a role in their health and survival, and the proportions shift with the seasons and availability. This diversity and reliance on natural foods underline the evolutionary roots of the hunter-gatherer diet.

"They drink muddy water, eat honey with larvas and even sometimes meat with animal waste."

Surviving the Ages: Skills and Traditions That Endure

When I think about the Hadza people, I am struck by how their daily life is a living example of survival skills honed over thousands of years. As one Hadza saying goes,

"The Hadza tribe lives life in its rawest form."

This rawness is not just about facing the elements, but about mastering the skills and traditions that have allowed them to survive on the edge of the Serengeti for generations.

Fire-Making Techniques: The Heart of Survival

Fire is at the center of Hadza life. Making fire is not just a practical skill—it is essential for warmth during cold nights, for cooking food, and for protection from wild animals. The Hadza use traditional fire-making techniques, often rubbing two sticks together or using a fire drill. This skill is taught from a young age, and every member of the group learns to master it. Without fire, survival in the bush would be almost impossible.

Traditional Foraging: Digging Sticks and Tubers

Foraging is another vital part of Hadza survival. The Hadza use digging sticks to unearth tubers, which are a reliable food source, especially during the dry season when other foods are scarce. Their knowledge of edible plants, roots, and berries is extensive. They know which plants are safe to eat and which are poisonous, a skill passed down through generations by watching, listening, and participating alongside elders.

Hunting Techniques: Chasing and Trapping

Hunting is both a skill and an art for the Hadza. They chase rock hyraxes, antelopes, and even baboons, sometimes spending nights waiting at waterholes during the dry season when animals come to drink. Their hunting techniques are varied, including tracking, trapping, and ambushing. The Hadza’s deep understanding of animal behavior and the landscape gives them an edge in the wild.

Poisoned Arrows: Specialized Knowledge

One of the most remarkable survival skills is the use of poisoned arrows. The Hadza carefully extract poison from the Adenium plant, a process that requires specialized knowledge and caution. The poison is applied to their arrow tips, making their hunting more effective and increasing their chances of bringing down larger game. This use of natural resources is a testament to their detailed understanding of the plants around them.

Oral and Participatory Knowledge Transmission

What stands out to me is how these survival skills are passed down. The Hadza do not have written records. Instead, knowledge is transmitted orally and through active participation. Younger tribe members learn by joining in hunts, foraging trips, and communal tasks. Elders teach by example, sharing stories and demonstrating techniques. This participatory approach ensures that every new generation is equipped with the skills they need to survive.

Social Structures and Egalitarian Traditions

Survival for the Hadza is not just about individual skill—it is about community. Food is always shared, and everyone contributes to the group’s well-being. This sharing reinforces egalitarian social bonds, contrasting sharply with more hierarchical societies. There is a strong sense of collective responsibility, and no one is left behind. The act of sharing, whether it’s honey gathered from a tree or meat from a successful hunt, is central to their way of life.

Fire-making techniques are essential for warmth and cooking.

Digging sticks are used to gather tubers, a key food source.

Poison from Adenium plants is carefully prepared for hunting arrows.

Oral teaching and active participation ensure skills endure across generations.

Food sharing maintains strong social bonds and collective survival.

These survival skills and traditions are not just relics of the past—they are living, breathing practices that continue to define the Hadza’s existence today.

Life in the Hadza: Raw, Unfiltered Existence

When I think about life in the Hadza, I am struck by how different it is from the world I know. The Hadzabe tribe lives each day in a way that is both ancient and immediate, facing the rawness of nature without any filters. Their hunter-gatherer lifestyle means survival depends on what the land offers, and nothing is sanitized or guaranteed. Every meal, every drink, and every decision is shaped by the unpredictability of the wild.

Undomesticated Living: Eating and Drinking from Nature

The Hadza’s daily existence is a lesson in adaptation. There are no taps or purified water; instead, they drink directly from muddy pools or streams. As one observer put it:

"They drink muddy water, eat honey with larvas and even sometimes meat with animal waste."

This undomesticated approach to food and drink is not a choice, but a necessity. Honey is often scooped straight from the hive, larvae and all. Meat, sometimes still bearing traces of animal waste, is consumed without hesitation. The Hadza do not shy away from these realities; they accept them as part of their world. This raw survival challenges modern perspectives on hygiene and food safety, but it also reveals a remarkable human resilience.

Constant Exposure: Sharpened Survival Instincts

Living so close to nature means the Hadza are always exposed to the elements. There are no walls to block the wind, no roofs to keep out the rain. Every day brings new challenges—heat, cold, insects, and wild animals. This constant exposure creates a sharper survivalism. Children learn early to recognize animal tracks, to find edible roots, and to avoid danger. Their senses are tuned to the environment in a way that is hard to imagine from a modern perspective.

Social Life: Hunting, Foraging, and Camp Consensus

Social structure is another key part of life in the Hadza. The tribe organizes itself around hunting parties and foraging groups. Men often go out in small teams to hunt game, while women gather berries, tubers, and honey. Decisions about where to camp or when to move are made by consensus, not by a single leader. This flexible, egalitarian system helps the Hadza manage the unpredictability of their environment. Everyone’s voice matters, and cooperation is essential for survival.

Harsh Realities: Embracing Nature’s Rawness

The Hadzabe tribe traditions are shaped by the harsh realities of their world. Food is not always plentiful, and sometimes it is dirty or carries risks. Dealing with animal waste on meat or drinking muddy water is part of daily life. These challenges might seem unthinkable to outsiders, but for the Hadza, they are simply facts of existence. Their ability to adapt and endure speaks to a deep-seated resilience and adaptability.

Shared Risks and Strong Bonds

Facing constant uncertainty, the Hadza form strong bonds through shared risks. Whether it is a dangerous hunt or a difficult dry season, everyone depends on each other. The unpredictability of their environment means that cooperation and mutual support are not just values—they are necessities. These connections create a sense of belonging and trust that is central to Hadza life.

Language Hadzane: The Core of Cultural Identity

Perhaps the most distinct marker of Hadza identity is their language, Hadzane. This language, filled with unique clicks and sounds, is more than just a way to communicate. It is a core pillar of their culture, connecting generations and strengthening group cohesion. In a world where everything else is unpredictable, Hadzane remains a constant thread, tying the community together and preserving their unique heritage.

Exploring the Challenges: Modern Pressures on Ancient Ways

Living with the Hadza tribe, I quickly realized that their ancient way of life—hunting with bows and arrows, foraging for wild honey, and drinking from muddy waterholes—faces challenges far beyond the daily uncertainties of the savanna. The Hadza tribe lifestyle, rooted in nomadic hunter-gatherer traditions near Lake Eyasi, is now at a crossroads. Modern pressures threaten not just their land, but the very survival of their culture and knowledge.

Encroachment and Shrinking Territory

One of the most visible challenges is land encroachment. Over the past century and a half, the Hadza have watched their traditional territories shrink. Agriculture, livestock grazing, and the creation of protected areas have all played a part in restricting their movement. Where the Hadza once roamed freely, following game and seasonal plants, they now find fences, farms, and boundaries. This loss of land means fewer places to hunt rock hyraxes, antelopes, and baboons, and less access to the wild foods that have sustained them for generations.

Encroachment by farmers and herders reduces hunting grounds.

Protected areas, while preserving wildlife, often restrict Hadza access.

Traditional foraging routes are blocked or destroyed.

Partial Sedentarization and Mixed Lifestyles

As their territory shrinks, some Hadza are adopting mixed lifestyles. While a minority still live exclusively as nomadic hunter-gatherers, many now spend part of the year in small settlements or villages. Here, they may trade for maize or tobacco, or take up occasional farm work. This partial sedentarization brings new comforts but also risks. The more time spent away from the wild, the greater the chance that traditional foraging knowledge and hunting skills will fade.

“Mixed lifestyles may lead to loss of pure foraging knowledge,” one anthropologist told me. “It’s a delicate balance between adaptation and cultural survival.”

Land Rights and Cultural Survival

Land rights remain a contentious issue. The Hadza have deep historical roots in this region—over 50,000 years by some estimates—but legal recognition of their land is limited. Disputes with neighboring groups and government authorities are common. Without secure land rights, the Hadza’s ability to maintain their nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle is under constant threat, putting their cultural survival at risk.

Land rights are often unclear or contested.

Encroachment disrupts access to vital resources.

Cultural preservation depends on secure territory.

Health, Lifespan, and Modern Influences

Interestingly, modern diseases like diabetes and heart disease are mostly absent among the Hadza. However, their average lifespan is impacted by high infant mortality and the dangers of living “on the edge.” As contact with outsiders increases, so does the risk of new illnesses and dietary changes that could undermine their health.

Cultural Dilution and Legal Exceptions

Perhaps the greatest risk is cultural dilution. As more Hadza children grow up near towns or in mixed communities, the unique Hadzane language—with its distinctive clicks—and the skills needed to survive in the wild may be lost. While some legal exceptions allow the Hadza to hunt within protected zones, these are fragile agreements that can change with shifting policies.

Traditional knowledge is at risk as lifestyles change.

Legal exceptions for hunting are not always guaranteed.

Language and identity face erosion from outside influences.

The Hadza tribe’s way of life is a living link to our shared human past. But as modern pressures mount, the future of these nomadic hunter-gatherers—and their unique culture—remains uncertain.

A Day Among the Hadza: Personal Reflections on Survival

“For the next three days, I’ll be a part of their tribe and witness their way of life.” With these words echoing in my mind, I stepped into the world of the Hadza tribe, eager to experience firsthand what it means to live a true hunter-gatherer lifestyle. My immersion with the Hadza near Lake Eyasi in Northern Tanzania was more than a journey—it was a lesson in survival skills, community, and the enduring connection between people and the land.

The Hadza tribe lifestyle is shaped by a deep relationship with their environment. From the moment I arrived, I was struck by the simplicity and directness of their daily routines. Water, for example, is not always clear or clean. I watched as tribe members drank from muddy pools, a reminder of the raw realities of survival. Meals were equally humbling and fascinating. Honey, rich with larvas, was a prized treat, and meat was sometimes eaten with traces of animal waste. These experiences challenged my own perceptions of what is edible and safe, highlighting the Hadza’s remarkable adaptation and resilience.

Participating in the Hadza’s daily activities offered a window into the beauty and challenge of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. I joined them on a hunt, moving quietly through the bush, every sense alert. The unpredictability of the hunt was palpable—sometimes we returned empty-handed, other times with a small animal to share. The respect shown for each animal hunted was profound, a stark contrast to the detachment often seen in modern food systems. Honey harvesting was another highlight, involving careful negotiation with wild bees and an intimate knowledge of the landscape. These moments revealed the Hadza’s survival skills immersion, honed over thousands of years.

Meals were communal, eaten around small fires in the open air. There was a sense of egalitarian camaraderie—food was shared equally, and everyone contributed to the tasks at hand. The Hadza’s social structure is notably egalitarian, with decisions made collectively and resources distributed fairly. This fostered a sense of trust and mutual reliance within the camp, essential for survival in such a challenging environment. I was welcomed as an equal, despite being an outsider, and quickly learned that every member’s contribution mattered.

Living among the Hadza, I felt a raw connection to nature that is rare in modern life. Their language, Hadzane, is filled with unique clicks and rhythms, echoing the sounds of their environment. Communication was sometimes a challenge, but gestures and shared experiences bridged the gap. I was reminded that survival is not just about physical endurance, but about social bonds and cultural knowledge passed down through generations.

Reflecting on my time with the Hadza, I realized how modern life often distances us from these primal roots. Our conveniences and technologies, while making life easier, can also disconnect us from the natural world and from each other. The Hadza’s way of life is not just about survival, but about living in harmony with the land and with one another. Their traditions offer a powerful perspective on sustainability, community, and what it truly means to thrive on the edge.

My personal experience with the Hadza tribe lifestyle has left a lasting impression. It humanized the challenges and joys of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle and deepened my appreciation for the cultural richness of one of the world’s last remaining hunter-gatherer societies. In a world that is rapidly changing, the Hadza remind us of the enduring strength found in simplicity, connection, and respect for the earth.